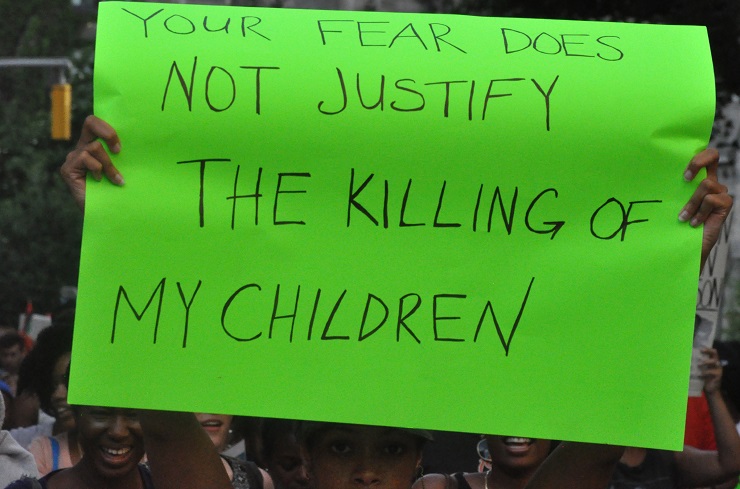

Berlin Stands with Charlottesville by majka czapski // Flickr CC Licence Majka Czapski

Chris Crass is a longtime organizer, educator, and writer working to build powerful working class-based, feminist, multiracial movements for collective liberation. He is one of the leading voices in the country calling for and supporting white people to work for racial justice. He joined with white anti-racist leaders around the country to help launch the national anti-racist network Showing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ), which works in white communities for racial justice. Rooted in his Unitarian Universalist faith he works with congregations, seminaries, and religious and spiritual leaders to build up the Religious Left. He lives in Louisville, KY with his partner, and their two kids. Learn more about Chris here. I spoke with Chris and Richie Schulz, Philadelphia Yearly Meeting’s community engagement fellow, on September 6th, we talked about the current political moment, organizing white folks for racial justice, and the stake white people have in that work. This is the fourth of five posts from that conversation. This wasn’t an interview per se, but a conversation with each of us contributing.  Lucy Duncan: Okay, this question is something that you and I both write about a lot. What's your sense for what's at stake for white people, particularly white people of faith in the struggle for racial justice?

Lucy Duncan: Okay, this question is something that you and I both write about a lot. What's your sense for what's at stake for white people, particularly white people of faith in the struggle for racial justice?

Chris Crass: Yeah, absolutely. I came into anti-racist work really having grown up in an extended working-class family where there was a lot of white people who were racist. But my mom, she would argue with them and there was all kinds of sexism directed at her, kind of dismissing her opinions and her leadership, but as a young kid, my mom saying “yes” to anti-racism really saved my life in a lot of ways. Her saying "no" to them and saying "yes" to justice and racial justice and teaching me about Dr. King and Rosa Parks and Jackie Robinson really saved my life from a background that very much could have prepared me to be a right-wing racist, who really looked at the world from a place of fear, distrust, resentment and hatred.

For me, coming into that, carrying the tradition of Anne Braden and Paul Braden in the South who were organizing in the 50s and 60s from this perspective of “white supremacy does incredible damage to the imagination, to the heart, to the values, to the sense of self of white people.” That’s what whiteness and racism was intended to do from the beginning. European indentured servants were forming families, forming friendships, forming communities with enslaved Africans, with indigenous people. Laws were enacted to prevent people coming together, there were rewards for white people to only align with the ruling class, and the capitalist, racist agenda, there was punishment for people of color (POC) and punishment for white people who stepped out of that white racist world view. I do this work because white people's lives are at stake in the fight against white supremacy, our hearts, our minds, our souls, our children, our community. The crisis of drug addiction, of suicide, of depression, of isolation that is in so many white communities, white working-class and middle-class communities is a byproduct of white supremacy. These developments are directly about the impact of white supremacy on white people’s culture, white people's lives, white people's sense of the world, white people's sense of themselves.

I do this work because I want to end the nightmare of white supremacy for POC, but I also want to end it in white communities that literally train and socialize white kids like mine to be soldiers of racism whether they are liberal implementers of more of a managerial white supremacy in a diversity model that says, "all are welcome, but if POC come in they will be treated horribly and their labor will be over-exploited” or more overt in their racist ideology. For me it’s how do we create opportunities for white people to be both on the right side of history and also to reject this monstrous system that impacts our lives as white people, our communities, our families, the ways that we relate to each other and the ways that we are in the world.

I do this work because I want to end the nightmare of white supremacy for POC, but I also want to end it in white communities that literally train and socialize white kids like mine to be soldiers of racism whether they are liberal implementers of more of a managerial white supremacy in a diversity model that says, "all are welcome, but if POC come in they will be treated horribly and their labor will be over-exploited” or more overt in their racist ideology. For me it’s how do we create opportunities for white people to be both on the right side of history and also to reject this monstrous system that impacts our lives as white people, our communities, our families, the ways that we relate to each other and the ways that we are in the world.

Yes, there are real benefits around white privilege, benefits that were specifically granted to indentured Europeans and working-class white people to separate us and POC from multiracial democracy. White privilege is specifically trying to get white people to buy into whiteness and away from a multiracial democracy that embraces and affirms all of our humanity. Racism is a disease and a poison and a monstrosity in white communities that we need to save white people from as we work to destroy white supremacy's impact institutionally and culturally on communities of color.

Lucy Duncan: Yeah, I totally agree and briefly I'll just say the violence that is white supremacy, the violence that is necessary to maintain and uphold white supremacy, it creeps into white families, it creeps into all of our interpersonal relationships and it's disruptive. I was in a white affinity group as part of Niyonu Spann's Beyond Diversity 101. We told the stories of our white ancestors and the patterns of abandonment of each other as white people, abandonment because you're gay, because you somehow don't fit the white norm, abandonment for all kinds of reasons, as a way to say, “we're going to leave you behind if you don't uphold this horrible system." It's so deep.

Lucy Duncan: Yeah, I totally agree and briefly I'll just say the violence that is white supremacy, the violence that is necessary to maintain and uphold white supremacy, it creeps into white families, it creeps into all of our interpersonal relationships and it's disruptive. I was in a white affinity group as part of Niyonu Spann's Beyond Diversity 101. We told the stories of our white ancestors and the patterns of abandonment of each other as white people, abandonment because you're gay, because you somehow don't fit the white norm, abandonment for all kinds of reasons, as a way to say, “we're going to leave you behind if you don't uphold this horrible system." It's so deep.

I have it in my family: my grandfather abandoned a whole family before he met my grandmother. He didn't physically abandon my mom and her brothers, but he emotionally abandoned my mom. It's so soul-sucking, our souls are mutilated and deeply deformed from this stuff and we don't get to be who we're supposed to be because we are invested and participating without our consent, right? Initially we are acting without our consent, and then at some point we choose and are upholding it. If we get a little bit awake, then we can begin to choose, to resist, to act from a more human place. That's huge motivation for me, motivation in terms of my own development. One result of the shifting and waking up as a result of doing anti-racist work is that my heart is a whole heart now. I get to be a much more whole person. I'm always working at it. I don't take off my white privilege, my whiteness, but I think there is a completely different relationship with the world, with my white family, with my white son, with my white brothers and sisters as well and with people of color since I have begun to strive to embody a different way to be white.

Related posts:

Now is the time of monters: A conversation with Chris Crass, part 1

The precarity and possibilty of this political moment: A conversation with Chris Crass, part 2

If this faith were a bowl, could it hold me? A conversation with Chirs Crass, part 3

Organizing white people for racial justice: A conversation with Chris Crass, part 5