Iowa community members at a vigil for people killed in the mass shooting in Atlanta. Jon Krieg / AFSC

Like many people, AFSC staff were devastated to learn of the mass shooting in Atlanta—which took the lives of eight people, including six women of Asian descent. The killings come amid a sharp rise in reports of anti-Asian violence and harassment across the U.S. during the pandemic.

Today, it’s as critical as ever that we do all that we can to stand with the Asian community and confront anti-Asian violence—and all forms of racism and white supremacy.

Here a few AFSC staff members share their perspectives in the wake of the shooting in Atlanta.

Jiway Tung

Country Representative, Indonesia

Out of this horrible tragedy, I’m glad to see increased attention towards anti-Asian hate. At the same time, unfortunately this is not something new. In the Chinese Massacre of 1871, 19 Chinese were murdered in Los Angeles during a racial riot. The Page Act of 1875 prohibiting Chinese women from coming to the U.S. was the first restrictive immigration law at the federal level, followed by the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act banning the immigration of Chinese men.

For me personally, starting in first grade I had to get used to being called “chink” and the fights, bullying, and being chased by groups of white boys. When my family moved from Queens to Long Island, rocks were thrown at our house and the fights, bullying, and racial slurs continued through high school. College was where I first learned about liberal spaces and the accompanying denial of racism. After getting tired of the college administration’s inaction in addressing racism, I was part of a group of students led by African American women that organized a takeover and sit-in on the administration building for five days.

Asian Americans are very diverse in skin color, national origin, religion, languages, food etc. Perhaps what we have in common is regardless of whether we were born in the U.S. or not, we are considered perpetual foreigners. Meeting (white) U.S. citizens abroad, after telling them I’m from New York, I can’t count how many times I’ve been told that I don’t look American or that my English is pretty good.

May we respond to the killings of Asian women in Atlanta with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “fierce urgency of now” that is needed to face and never turn away from white supremacy in all its manifestations.

Joelle Eliza Lingat

Detention Attorney, Newark Immigrant Rights Program

I feel a lot of weight on my shoulders as a young mother-to-be, bringing forth Asian American life into this society that has imbued such Asian American hate. For my entire life, I have lived in the liminal space at the intersections of my identities within the diaspora and wonder if my child will also be scorned by this constant lack of belonging. How can I prepare them for a world that lacks the compassion and ability to love them fully and unconditionally? How will we hold ourselves accountable to future generations when our country has succumbed time and time again to the violence and wrath of xenophobia and greed?

The most recent tragedies in the U.S. are mirrors of the ongoing atrocities worldwide. Just earlier this month, in my home country of the Philippines, our sitting president gave marching orders to “Kill them all,” leading to the Bloody Sunday massacre of nine civilian activists. It would be a travesty to not link the recent attacks on Asian Americans domestically to the plague of U.S. imperialism around the world historically from nuclear testing in the Pacific, the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the wars in Korea, Vietnam, and countless other countries.

If there is anything that we have learned from this year of unprecedented tragedy is that the people’s movements will only be successful if we link arms beyond racial lines, borders, and even the limitations of our imaginations as we create a new world where we can be confident that all life will be acknowledged with dignity and respect. It is not enough to stop Asian hate, but we must reject settler colonialism, anti-Blackness, ableism, and all the plagues and afflictions of our current society that puts profit over people. For each other, for the future, and together, we must win!

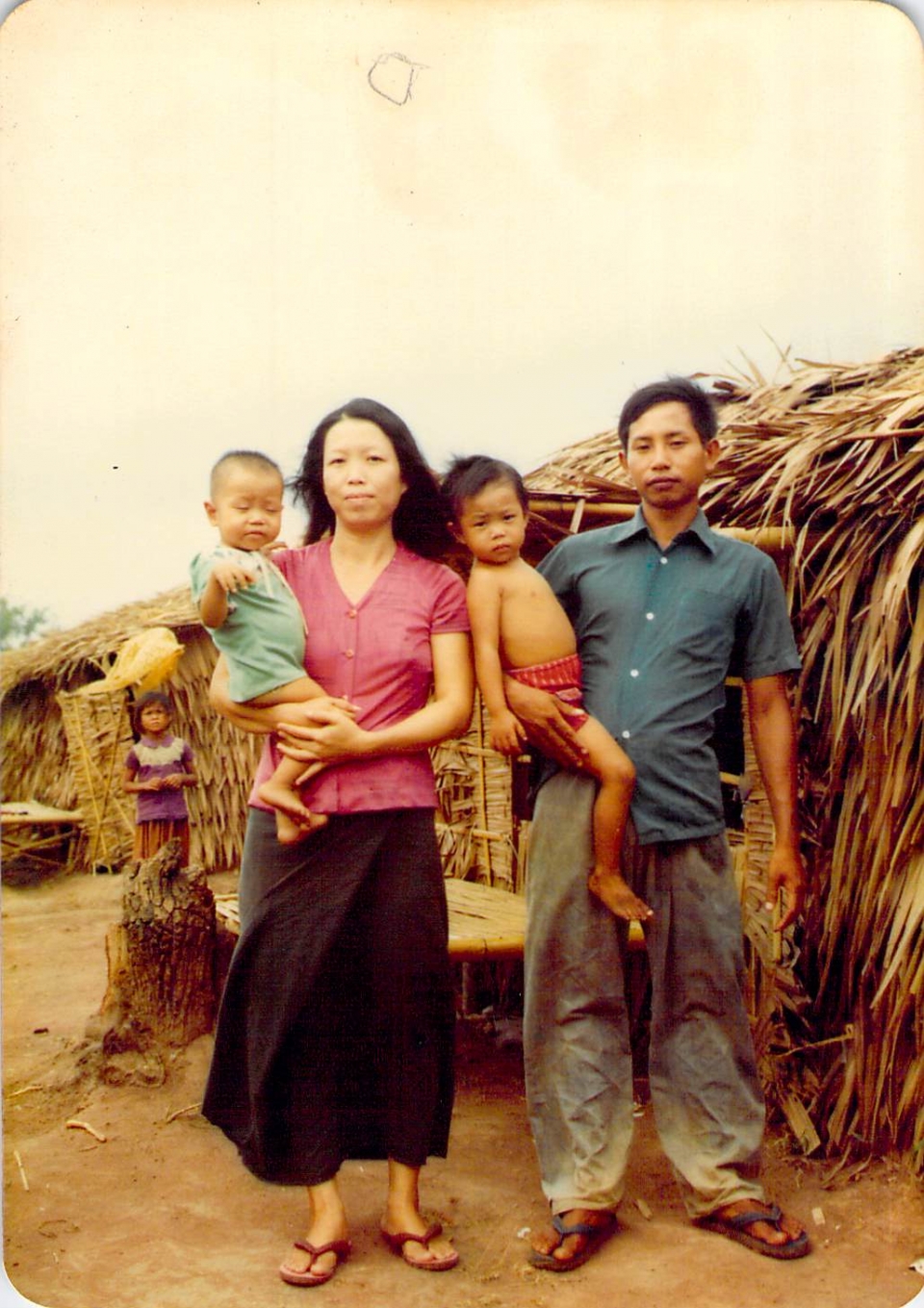

Sok Be

Director of Grants

No one in my family is remotely political. My parents were very adamant from the time that I was young, that we not get involved in politics. Their experience of politics was based on their experience in Cambodia, where being aligned with the wrong political faction could get you killed. So we don’t talk about politics and we definitely do not talk about political identity.

I remember one of the most painful conversations I had with my brother was when he told me not to bring my politics into his house and to his daughters and if I did, I wouldn’t be allowed to see my nieces again. While it is his right as a parent, I also shared with him that I also have the right to defend our family and our identity, as well. I can’t sit by when I hear someone say at a family gathering that they don’t like to hear the “ching ching chong chong” that my parents speak when they are around them.

So when people ask me how I’m doing after Atlanta. I really don’t have an answer. I sit with my own internal family dynamics. I also have my own experiences of being harassed for being Asian, from insensitive children pulling their eyes at the corners to having an object thrown at my head and someone yelling “chink” as they ran away.

Yet at the same time, I want to talk about the bigger picture: This is an opportunity for Asian Americans to share the nuances of our Asian American identity. The model minority stereotype is a paper tiger—something that appears to be strong but crumples when you examine it. The spectrum of who is Asian American runs from newly arrived refugees from Myanmar to Silicon Valley Tech CEOs.

How am I doing? I’m still working through it.

Chia-Chia Wang

Organizing and Advocacy Director, Newark Immigrant Rights Program

Not being raised in this U.S. and coming to this country as an adult can be a very different experience. Over the past 20 years in the U.S., I experienced some biases and verbal or physical insults but none of them resulted in deaths or broken family. I usually just keep to myself, sometimes shared my experiences with my partner or a friend, then just told myself “it's unfortunate.”

There are several incidents that particularly hurt me and I will remember probably for the rest of my life. I remember my ex-partner, who is Chinese, got spat on his face by a group of teenagers. I’ve gotten spat on my shoes. Once someone in the subway sitting next to me said I smelled like fish. There have been countless times people started mimicking kung-fu in front of me. In the beginning of the pandemic, a woman saw me enter the subway car with my toddler daughter, and she left the train in the next stop.

After the shooting in Atlanta, I think now there is an opportunity for society as a whole and individuals to recognize there is long history of hidden racism and bias towards Asian and Pacific Islanders, and engage in deeper conversations that don't compare one struggle with another, and change the status quo.

Joan Marshall-Missiye

Monitoring & Evaluation and Learning Advisor, International Programs

The anti-AAPI rhetoric, hate crimes, scapegoating, discrimination, and hate incidents are not new; they are built off generations of violence against the AAPI community. We have been blamed for disease outbreaks before, we have been incarcerated in camps, we have been murdered just because the U.S. automobile industry faced competition from Japan, we have been murdered by police, we have been colonized, deported, and we have been erased. We barely learn this history in the classrooms. We barely dig into the nuances and layers of the legacy of racism in this country.

A classmate called me “China girl” throughout middle school. Teachers heard him but said nothing, as if that did not affect me at all. Another classmate touched my hair and said it looked like pubic hair. The students around us, including a few who I thought were my friends, laughed. In college, someone in my dorm said he will give me a menu of dog meat as a Christmas present. These incidents paint the ignorance and the limited race education, whether at home or at school, and exposure these classmates have had. I myself did not receive any kind of nuanced, intersectional race education while at school.

As a parent, I vow to make sure my child will have a better race education than I did. As an Asian and Black child, she is an interruption to the white supremacist system and I want her to know that that is precisely her power. She will know that racial differences and bias exist. She will not be color-blind. She will stand with her BIPOC brothers and sisters and not let white supremacy pit her against anyone. We need to affirm that it is all of us against white supremacy. And she will make sure her white friends understand that destroying white supremacy does not mean being anti-white.