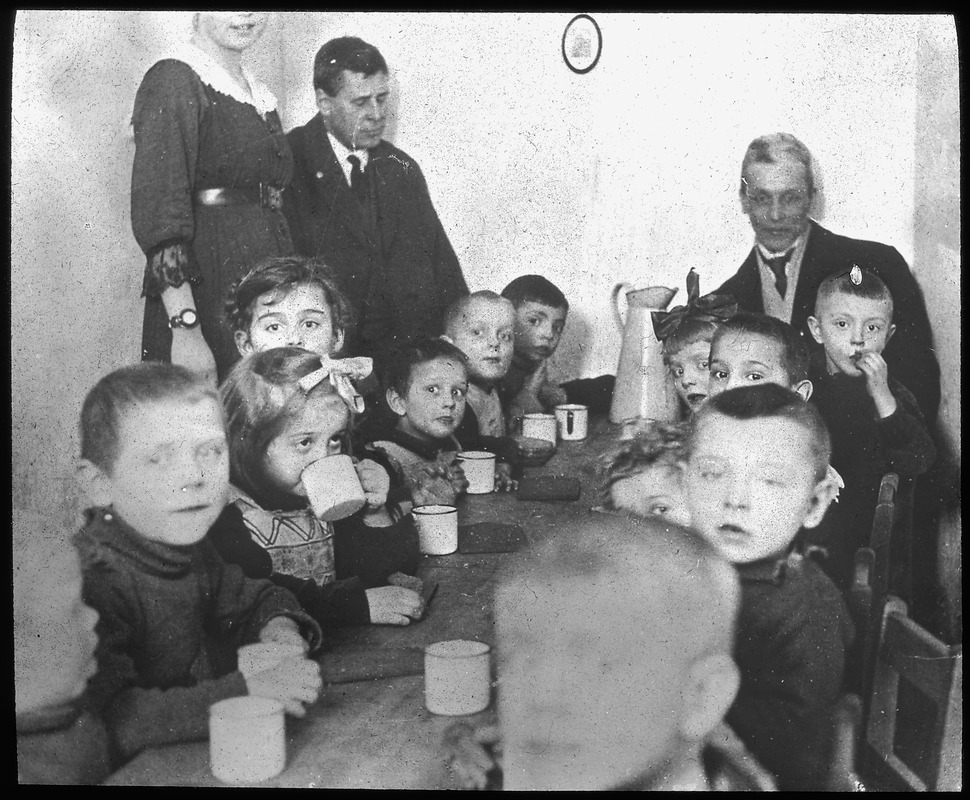

Providing food to children in Berlin, Germany in 1920. Photo: AFSC Archives

In the wake of World War I, Quakers and the newly formed AFSC began providing food for children in danger of starvation in war-torn Europe. In the following years, they would feed hundreds of thousands of children in Germany, Austria, Poland, and Russia. Although they had no way of knowing it, they were beginning a tradition of working for food justice that would last for over a century.

As defined by the United Nations, the right to food is “the right to have regular, permanent and unrestricted access—either directly or by means of financial purchases— to quantitatively and qualitatively adequate and sufficient food corresponding to the cultural traditions of the people to which the consumer belongs, and which ensure a physical and mental, individual and collective, fulfilling and dignified life free of fear.”

For over a century, AFSC has championed that right. Rooted in Quaker values, we work for a world where no one goes hungry, where communities have the resources they need to thrive, and where food systems promote equity and stewardship of our environment.

Today, it would be difficult to find any organization in the world that has worked for food justice for as long, in as many different places, and in as many ways. Here we look back at our century of work for food justice.

Post World War I to 1930s

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visits coal mining families in West Virginia. Photo: AFSC Archives

AFSC’s early work of providing food aid to people impacted by wars or other social or natural disasters continued through World War II and beyond to the present-day genocide in Gaza. Over the years, our efforts have taken different forms to meet the needs of the communities we work with.

In the 1920s and 1930s, AFSC provided food aid in mining communities in Kentucky, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. Working with local partners, we supported cooperative gardens. AFSC’s executive secretary at the time, Clarence Pickett, also formed close connections with Eleanor Roosevelt, who traveled the country and saw firsthand how the Great Depression was affecting ordinary people. That helped AFSC influence federal New Deal policies that laid the foundation for today’s social safety net. It was one of the earliest examples of AFSC advocating for systemic change and sustainable solutions based on our experience with communities facing these problems.

1940s-1960s

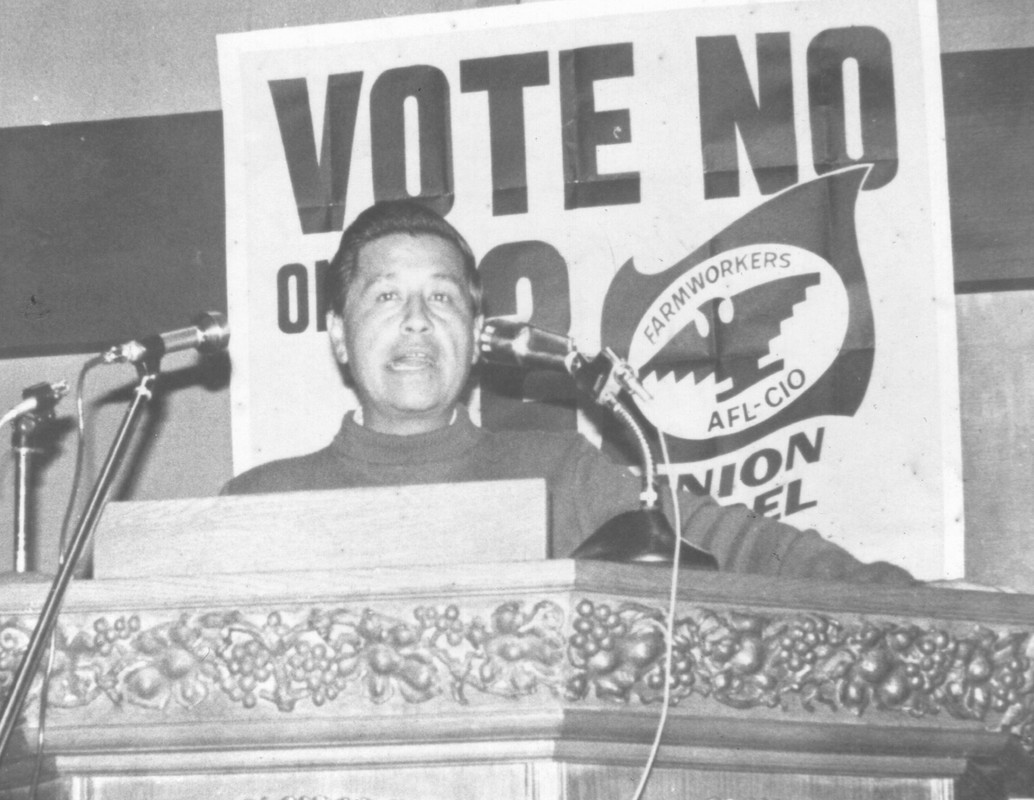

Labor leader Cesar Chavez, who headed the United Farm Workers union. Photo: AFSC Archives

The mid-20th century marked a shift toward addressing the root causes of hunger and inequality. AFSC’s work made more direct links between food security and labor rights, civil rights, and other struggles for justice.

In the 1950s, AFSC supported migrant farmworkers organizing for basic services, such as access to water and the elimination of tin-shack public housing. This work expanded into Proyecto Campesino in Visalia, California, which supported political organizing, informed immigrants on issues such as naturalization, and offered citizenship classes. We also helped them advocate more effectively for themselves when interacting with powerful growers and legislators.

Later, AFSC staff supported the struggle to establish the United Farm Workers union. We provided meeting places, collected funds for strikers, and paid the salary of the union’s chief negotiator. In 1975, UFW head Cesar Chavez acknowledged how essential AFSC’s support had been to the UFW. In turn, we acknowledged the great value of participating in the union’s “practical demonstration of a nonviolent movement.” AFSC’s work with farmworkers continues today in California’s Central Valley, Oregon and Washington, New Mexico, and many communities around the world.

During the 1960s, AFSC collaborated with the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and many others in the Poor People’s Campaign. The campaign brought hunger and poverty to the forefront of American consciousness, tying them to the broader issues of economic and racial inequity. It also created a coalition of poor and working people.

A few months after the Poor People’s Campaign encampment—known as Resurrection City—closed, “food programs were launched in the 1,000 neediest counties, as identified by the campaign’s objectives,” according to the National Museum of African American History and Culture. “A supplementary food program for mothers and children was also in progress by the end of the year. Additionally, Congress appropriated $243 million to expand and revamp school lunches to help feed hungry children.”

1970s-1990s

For years, AFSC worked closely with farmers in North Korea to increase food production as part of building peace on the Korean Peninsula. Photo: AFSC/Asia

Over the years, AFSC’s work grew to include supporting Indigenous people in reclaiming their rights. We also began to assist communities in their efforts to develop local, sustainable food systems and improve food security as part of building peace around the globe.

During the fishing rights battles in the Pacific Northwest in 1960s and ’70s, AFSC published the book “Uncommon Controversy.” The book championed Native respect for the environment and helped shift public opinion in favor of Native rights. Other AFSC efforts supported Native American land claims and economic alternatives.

In 1980, AFSC sent its first delegation to the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) as part of our longstanding work to promote peace on the Korean Peninsula. For years, we collaborated with North Korean farmers to enhance agricultural practices and boost crop production. Our work helped improve food security in a country facing food shortages, while bridging divides amid geopolitical tensions.

Relief efforts to Hurricane Mitch in Honduras, led by COMAL. Photo: AFSC Archives

Through much of the 1980s and beyond, AFSC worked in solidarity with liberation movements in Latin America to oppose U.S. military intervention and support base communities, or grassroots groups applying the ideas of liberation theology to challenge injustice. One result of that work in Honduras was the formation of Red de Comercialización Comunitaria Alternativa (COMAL/ Alternative Community Marketing Network). Today COMAL is an independent organization that trains farmers, facilitates access to credit and markets, and helps thousands of Hondurans develop a just alternative rural economy.

2000s to the present

Supporting local agriculture led by Indigenous communities in Guatemala. Photo: AFSC/Guatemala

AFSC's work for food justice work has evolved to reflect the multifaceted, interconnected nature of food systems around the world. Our projects span continents and approaches, but they are united in our unwavering belief in the power of communities to create just, sustainable food systems.

In Africa, AFSC has provided food assistance and support for community food production in several nations. That has included Burundi, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Mozambique, Somalia, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe.

In El Salvador and Guatemala, AFSC supports projects led by Indigenous communities. Among their efforts: promoting traditional food and medicine production, protecting water rights, and building food sovereignty.

In the United States, two AFSC programs—Roots for Peace in Los Angeles and Peace by Piece in New Orleans—help residents cultivate community gardens. The gardens serve as a means of community organizing while meeting food needs and promoting the use of heritage crops.

New Mexico’s AFSC People and the Land program, established in 1974, works with historic and land-based communities to protect access to land and water. We also help them grow food and medicine; increase access to local, healthy food by underserved children; stimulate local economies; and develop grassroots leadership.

Toward systems change

Residents and volunteers tend to the Hollygrove community garden, which is supported by AFSC’s Peace by Piece program in New Orleans. Photo: Peter Nakhid

Today, AFSC’s food justice work in the U.S. has increasingly focused on changing public policy. We have urged school districts to expand free meals for students, opposed restrictions on SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), and supported funding for WIC, a food assistance program for women, infants, and children.

Our current priorities include working with partners for a just and equitable Farm Bill. This massive piece of federal legislation protects SNAP and other food assistance programs. It also funds climate and conservation programs. And it supports small farms, urban food production, and rural communities.

In 2024, AFSC launched our No Hunger Summer campaign. The campaign supports activists in 12 states advocating their governors implement the federal SUN Bucks program. The program helps kids get the food they need while school is out by providing families with grocery-buying benefits.

At a national and international level, AFSC has recently partnered with the U.S. Right to Food Community of Practice and the Global Solidarity Alliance for Food, Health, and Social Justice. These groups recognize poverty and a corporate-driven food system as driving forces of both hunger and ecological damage. They also challenge the normalization of charity-based food assistance in favor of approaches based on rights, justice, and solidarity.

Over the past century, AFSC’s has worked to ensure the right to food for people around the globe. As we look to the future, we remain committed to this work as we continue to adapt to meet the changing needs of communities worldwide.