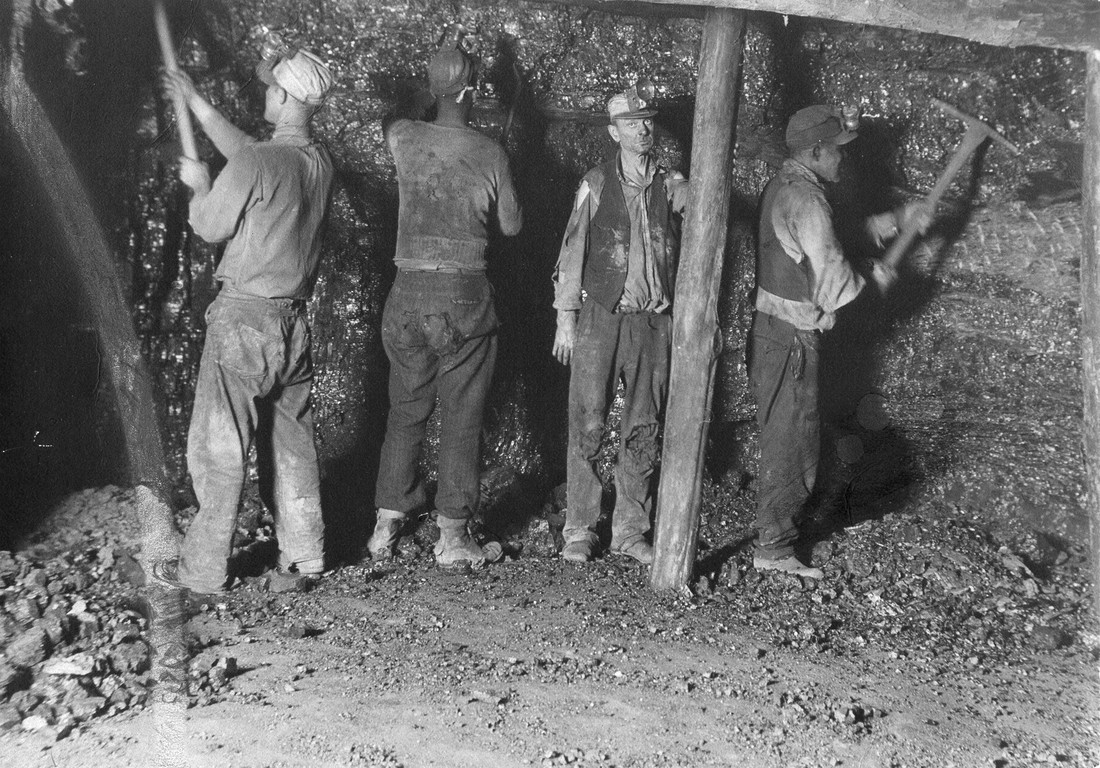

Coal miners in West Virginia. Photo: AFSC Archives

In happier times, my home state of West Virginia was known as a union stronghold. This tradition of labor action and struggle goes back to at least 1877, when railroad workers in Martinsburg set off something close to a nationwide general strike.

It continued as coal miners faced company and government repression, including brutal private mine guards, military intervention, airstrikes, legal injunctions, arrests, and imprisonments.

On my watch with AFSC, I’ve tried to support the struggles of unions on picket lines and at the policy level, ranging from metal workers to building trades to retail workers to teachers and school service workers. Sometimes things got a little wild.

I’ve made it an informal but unbreakable rule that whenever a good labor dustup happens within my range to drop everything and show up. I’m probably at least as loyal to unions as to the church I belong to … but if I had to choose between them, all bets are off.

For people unfamiliar with the labor movement, there are three main kinds of unions: craft unions representing primarily skilled trades; industrial unions representing workers at all skill levels in a sector; and public employee unions such as those representing education workers or government employees. The AFL-CIO, the largest U.S. federation of unions, comprises around 60 unions of different types and industries.

Where I come from, you’ll hear people talk about this or that union, but when they say the union, there’s one they have in mind: the United Mine Workers of America. Coincidentally or not, AFSC has a long history of supporting this union and the workers and communities it represents. Over a century ago, AFSC began providing food assistance and supporting economic alternatives for unemployed miners and their families. More recently, it has supported UMWA members in strikes, legislative struggles, mine safety, and corporate bankruptcies that threaten retirees and surviving family members.

People outside Appalachia may think of the UMWA, if at all, as a relic of an earlier age and a dying and dirty industry. In fact, even though its membership has dramatically declined over the last decades, it has arguably had the greatest impact on economic justice of any single organization. To the extent there’s still a middle class in this country, much of that is due to its direct and indirect influence.

The UMWA was founded in 1890 by the merger of the Knights of Labor Trade Assembly No. 135 and the National Progressive Miners Union. At a time when most unions represented skilled craft workers—mostly white, U.S. born, and male—the new union’s first goal was “to unite in one organization, regardless of creed, color or nationality, all workmen eligible for membership, employed in and around coal mines, coal washers, and coke ovens on the American Continent.” It was thus an early example of an industrial union, one that tried to represent all workers in a sector.

AFSC Archives

The union’s progress in West Virginia was slow and sometimes bloody. It was long known that the state was rich in coal and other minerals, but it required the coming of the railroads to make large-scale extraction economically feasible. Outside investors began gobbling up land and mineral rights and displacing mountain families, generally with the support of state politicians.

Let’s just say the good guys lost that one.

After wiping out most of the state’s old-growth forests, corporations began building coal camps in isolated mountain communities and instituting a system of total control, including company towns, company stores, company doctors, armed company mine “guards” to enforce obedience up to and including the use of violence, and company-controlled schools and churches. In many cases, workers were paid with company scrip or currency. Those with the temerity to organize or strike faced eviction from company housing, at the very least.

Companies actively recruited African Americans from the deep South, mostly white locals, and recent European immigrants to the camps. They hoped a “judicious mix” of different ethnicities would prevent union organization.

They were wrong.

From Colorado to West Virginia miners struggled, sometimes physically, for the right to organize, with something like guerilla warfare breaking out in my state during the Paint and Cabin Creek areas in 1912-1913. The struggle inspired writer Ralph Chaplin to pen the song “Solidarity Forever,” an international anthem of the working class. More militant struggles followed, including the 1921 Battle of Blair Mountain, the largest workers’ uprising in American history. So far.

It wasn’t until the New Deal era that the right of miners to organize was firmly established. For a generation or two…

And in the 1930s, the UMWA, under the leadership of the theatrical and sometimes confrontational John L. Lewis, launched the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which initiated vast organizing drives in steel, auto, rubber, and other industries. Unafraid to confront the highest levels of authority, he once said “you can’t mine coal with bayonets.”

During the CIO organizing drive, he proclaimed with characteristic flourish, “Let the workers organize. Let the toilers assemble. Let their crystallized voice proclaim their injustices and demand their privileges. Let all thoughtful citizens sustain them, for the future of Labor is the future of America.”

These organizing drives eventually won union recognition along with higher wages, better benefits, and improved working conditions for millions of American men and women. These new industrial unions, such as the United Auto Workers (UAW), would become strong financial and political supporters of the Civil Rights Movement.

This was not lost on the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., an ardent supporter of the labor movement. In his words, “During the ’30s, wages were a secondary issue; to have a job at all was the difference between the agony of starvation and a flicker of life. The nation, now so vigorous, reeled and tottered almost to total collapse. The labor movement was the principal force that transformed misery and despair into hope and progress.

“Out of its bold struggles, economic and social reform gave birth to unemployment insurance, old-age pensions, government relief for the destitute and, above all, new wage levels that meant not mere survival, but a tolerable life. The captains of industry did not lead this transformation; they resisted it until they were overcome. When in the ’30s the wave of union organization crested over our nation, it carried to secure shores not only itself but the whole society.”

The wave that Dr. King spoke of has unfortunately receded over the last 40 years, with devastating consequences. But it remains an example of what can be done when working people act in solidarity.

So year-round, but especially on May Day and Labor Day, I celebrate the victories and mourn the defeats of the world’s diverse labor unions. However, one union has pride of place. In more ways than one, it lit the way in many dark places.