AFSC banners in New Hampshire during the run up to the 2008 election. Photo: Jospeh Mehling

March 19 marks the 20th anniversary of the war in Iraq. The anniversary of events related to 9/11 and its aftermath calls us to reflect on the human and economic costs of the securitization framework that the U.S. developed in those years and continues today.

Over the past two decades, the U.S. government has extended military weapons, tactics, and criminalization into local communities. Meanwhile disproportionate military spending has starved those same communities of funding for human needs. Black and Brown communities have been most acutely affected after facing decades of overpolicing and disinvestment.

To date, the U.S. has spent $8 trillion on the “war on terror,” according to Brown University’s Cost of War Project. Those costs include the Department of Defense, State Department and USAID, Overseas Contingency Operations (war), medical and disability care for veterans medical /disability, and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which was created in the wake of 9/11.

That money funded the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the continued military airstrikes in conflict zones like Syria, Yemen, and Libya. But it also funded DHS efforts to militarize your town and many others across the U.S.

So-called “anti-terror” grants gave local police departments military-grade equipment, such as armored trucks and ballistics gear. That, along with what’s known as the federal 1033 program, allowed militarized equipment to flow into local communities. Highly militarized police forces started showing up at demonstrations, and peaceful protesters found themselves facing weapons of war.

DHS money also poured into U.S. Customs and Border Protection and funded equipment to militarize our borders and detain immigrants. It also funded surveillance programs targeting Muslims, Arabs, and social justice activists.

Movements for social justice worked to help the public understand how the Iraq war and “war on terror” was draining money from important human needs in our communities. In 2008, AFSC built on the tradition of Quaker war tax resistance, by creating tools and messaging that showed how the federal government was using our tax dollars to fund war, in part by diverting money from the things that communities need to thrive, such as housing, education, jobs, health care.

For years, Quakers and our allies demonstrated outside of post-offices on Tax Day, holding penny polls so that people mailing their taxes could indicate how they would prefer to spend their tax dollars. This work helped to build momentum against the “forever wars,” and eventually the withdrawal of troops from Iraq and more recently, Afghanistan. Today the Global Days of Action on Military Spending (GDAMS) continues that work by shining a light on increased military spending across the world, and that our government still spends billions on the military—the 2023 enacted levels for the Defense budget are 858.3 billion.

Communities of color are on the losing end of these policies. Post-9/11 domestic security infrastructure poured military money into local communities that, decades earlier, saw huge increases in spending on policing and prisons, fueled by the “war on drugs.”

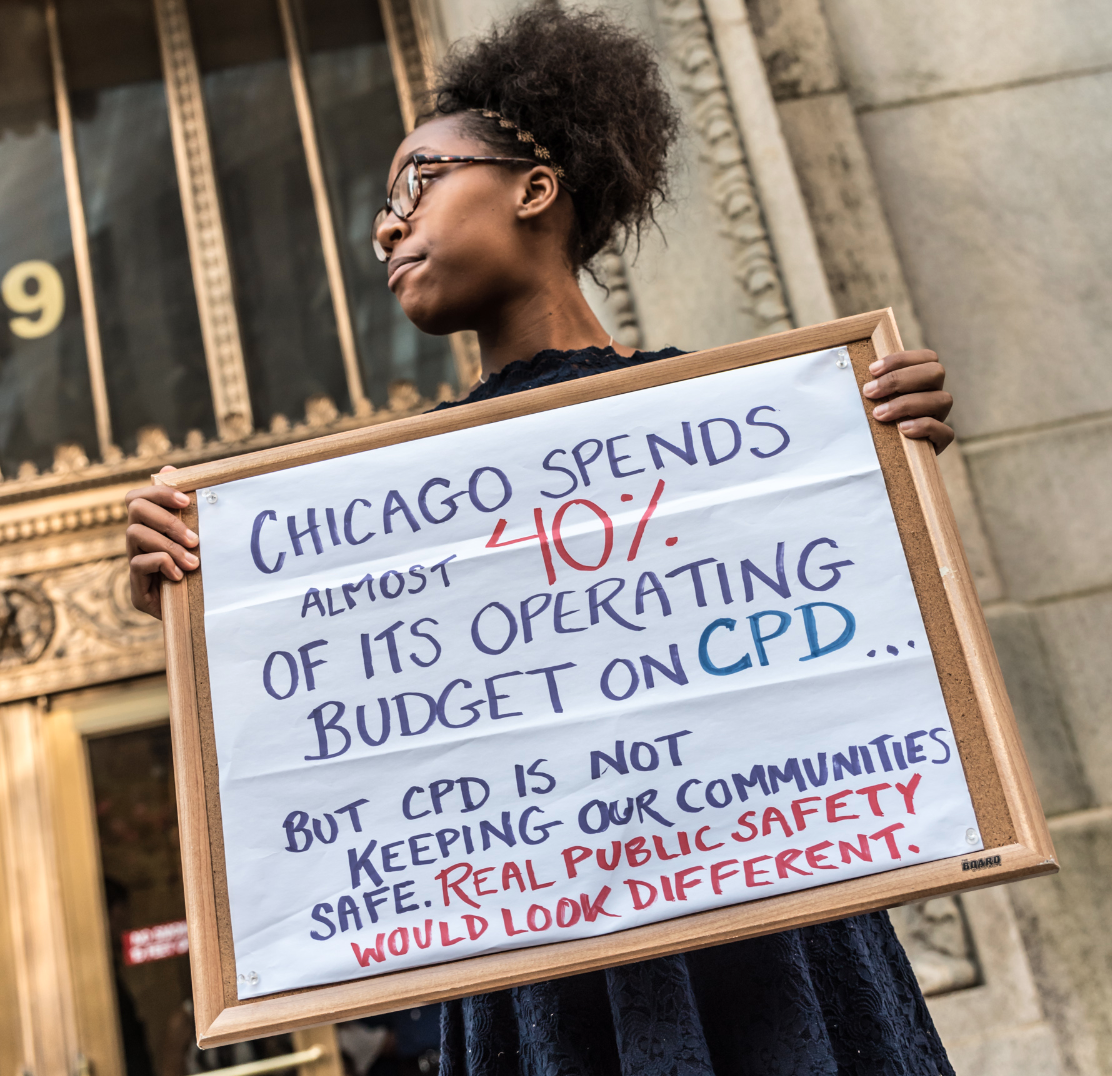

Photo: @loveandstrugglephotos

In addition, these same communities were more likely to be criminalized by the use of military equipment and tactics by civilian police that had been increasing since the ’70s, and accelerated during the “war on terror.”

The differences between police and the military started to blur. Police forces with militarized equipment are more likely to have violent encounters with the public—and militarized police are more likely to be deployed to communities with large Black populations.

Additionally, the army-to-police pipeline grew, with veterans who served as war fighters and occupying forces making up 19% of the law enforcement in the U.S., serving in small towns, suburbs, and cities across the country. Studies have noted that more citizen complaints are reported against veteran officers than other officers, and officers with military experience used their guns while on duty more than nonveterans.

All of this leaves Black and Brown communities facing both increasingly militarized and violent policing—and disinvestment in their communities caused by the disproportionate amount of money going into both military and police spending, at the federal, state, and local level.

Social movements called for divestment from policing and prisons using some of the same tools and messaging as the anti-war movement had. In the aftermath of the Ferguson uprising, the Movement for Black Lives launched a visionary policy platform that contained the influential Invest/Divest plank. These demands encourage campaigns to call for divestment from systems of harm and reallocation of that money to systems of care. AFSC was one of the ally organizations to endorse this platform and has made the Invest/Divest framework an important part of our North Star Vision document that outlines our work toward a world without prisons and police.

Today, the U.S. must examine the cumulative decisions we make as a country when choosing war, prison, and policing over other budget and policy priorities, such as health care, education, and employment. People need resources in their communities to help keep them healthy and safe. Communities need our government to look for peaceful solutions instead of fueling a new Cold War with Russia.

We can no longer accept that our continually growing military, police, and prison budgets are normal. We must keep pushing for divestment from war, prisons, and policing and a reallocation of those funds to life-giving, human-centered, systems of care for all.