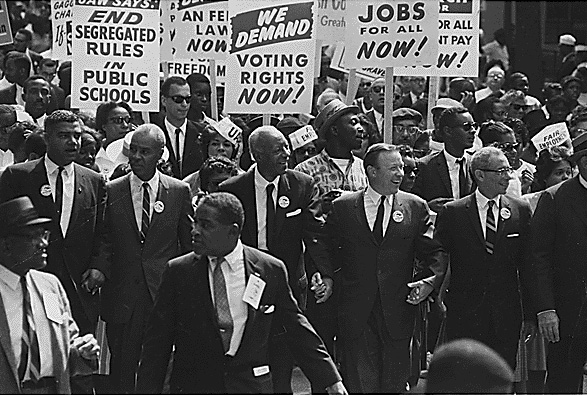

A. Philip Randolph photographed on the day of the March on Washington in 1963. Rowland Scherman / Public Domain

Two recent events made me think of A. Philip Randolph, an underappreciated hero of the labor movement and the African American struggle for freedom, justice, and equality.

The first was close to home. In West Virginia, Aug. 26 is officially Katherine Johnson Day in honor of the brilliant African American mathematician whose story is featured in Margot Lee Shetterly’s 2016 book “Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Who Helped Win the Space Race.” The book was made into a film of the same title that was nominated for Best Picture at the 89th Academy Awards.

Johnson was born in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia in 1918. A mathematical prodigy, she attended what is now West Virginia State University, a historically Black college, at age 15, graduating at 18 with majors in math and French. She was one of a handful of students to integrate West Virginia University’s graduate school.

In 1952 she joined the all Black Computing section at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, NASA’s forerunner, which was headed by Dorothy Vaughan, a fellow West Virginian. She would eventually play a major role in doing the math that made the lunar landing and other space advances possible.

At age of 97, Johnson received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2015. She died earlier this year at the age of 101. Her obituary in the New York Times began with these words: “They asked Katherine Johnson for the moon, and she gave it to them.”

The second event that reminded me of A. Philip Randolph was more somber. It was the Aug. 28 “Get Your Knee Off Our Necks” March on Washington for racial justice and an end to police brutality. The march was held on the 57th anniversary of the original march best known for Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.,

Neither of these events might have happened if not for the life and work of Randolph (1889-1979), an African American writer, editor, democratic socialist, union leader, and civil rights pioneer who made a huge mark on American history over several decades.

Born in Crescent City Florida, his father was an African Methodist Episcopal minister and tailor and his mother was a homemaker and skilled seamstress. Both were fearless advocates for racial justice.

Randolph headed to New York as a young man, working and attending college classes. He loved theater, and founded a Shakespearean society in Harlem, where he played many of the leading roles. Always concerned with the rights of Black workers, he edited radical monthly periodical The Messenger beginning in 1917, which the Department of Justice referred to as "the most able and the most dangerous of all the Negro publications." Randolph himself was called “the most dangerous Negro in America.”

In 1925, Randolph became the founding president of The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, a union representing Black workers on the luxury rail cars manufactured by the union-busting Pullman Company. The Brotherhood was the first Black-led union to be affiliated with the American Federation of Labor. Despite the name, the union also represented women who worked as maids on the rails.

It took a dozen years—and the help of New Deal labor legislation—but in 1937, the Brotherhood won major concessions from the company in what was probably the first major contract a white employer signed with a Black labor leader.

The Brotherhood was instrumental in opening the path to a decent livelihood for tens of thousands of Black workers. It’s no accident that one of the leaders of the 1950s Montgomery bus boycott that propelled Dr. King to national prominence was Brotherhood member E.D. Nixon.

Randolph also opposed segregation in labor unions and eventually helped end it, serving as a vice president of the AFL-CIO.

He was as comfortable playing hardball with presidents as with corporations. As the nation ramped up production during World War II, Randolph threatened a march on Washington to protest discrimination in federal employment and companies receiving government contracts—a move that pushed the Roosevelt administration into issuing Executive Order 8802 in 1941, which barred hiring discrimination in defense industries and federal agencies and created the Fair Employment Practices Commission.

This would eventually help open the doors of federal employment for Dorothy Vaughn, Katherine Johnson, and other brilliant “hidden figures” in the aeronautics and space industries.

After the war, Randolph founded the League for Non-Violent Civil Disobedience Against Military Segregation that went head to head against the Truman administration. The result was Executive Order 9981, which ended official discrimination in the U.S. military.

He was assisted in these efforts by Bayard Rustin, a brilliant Black organizer (and Quaker who worked with AFSC). When Rustin, a gay man, was attacked for his sexual orientation by U.S. senator and segregationist Strom Thurmond and others, Randolph responded by expressing complete confidence in Rustin, saying “I am dismayed that there are in this country men who, wrapping themselves in the mantle of Christian morality, would mutilate the most elementary conceptions of human decency, privacy and humility in order to attack other men.”

Rustin would later say of him that “no one has stood beside me in times of trial the way Mr. Randolph has. He is the only man I know who has never said an unkind word about anyone, or who refuses to listen to an unkind word about anyone, even though it may be true.”

Randolph and Rustin’s greatest effort was organizing the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which featured speeches and performances by Dr. King, the late Congressman John Lewis, NAACP leader Roy Wilkins, West Virginia-born labor leader Walter Reuther, James Farmer of the Congress of Racial Equality, singers Joan Baez and Bob Dylan, and many others.

Randolph himself spoke as well, saying that “we know that we have no future in a society in which 6 million black and white people are unemployed and millions more live in poverty.”

That march inspired generations of Americans, including those who marched this summer.

This is only a partial list of the accomplishments of an amazing life. This Labor Day, I’ll remember many of those who fought for workers’ rights, but Randolph holds a special place for me.

In the words of his beloved Hamlet, “He was a man, take him for all in all, I shall not look upon his like again.”