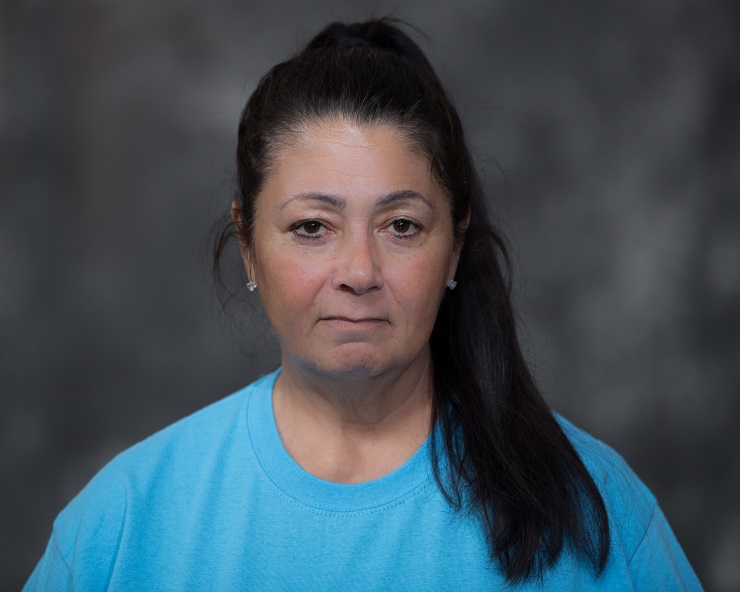

Denise Altvater Don Davis / AFSC

Denise Altvater serves as coordinator as the Wabanaki Youth Program in Maine. She has created a supportive web of connection and communication in a region where Native communities have been isolated and abused. With her leadership, the American Friends Service Committee's Wabanaki Program in Maine was instrumental in developing the first Truth and Reconciliation commission between a sovereign Tribal nation and a U.S. state. Recently, Denise has focused on offering decolonization workshops for faith communities.

Christina Elcock and Lucy Duncan open up a conversation with Denise to explore the importance of decolonization and why it’s vital in order to heal from the cracks and abuses of a dehumanizing system.

Lucy Duncan: Can there be wholeness without forgiveness?

Denise Altvater: Absolutely. And it wasn't easy for the people of faith group to understand that because in faith it's all about forgiveness. But they did, they understood. I showed them a picture of my daughter because they wanted to know what colonialism still looked like on the reservation. I passed it around but didn't tell them it was my daughter. This picture was taken maybe a week ago. When you look at this picture of her, all you can see is the pain of the world in her eyes. Her eyes, just, oh my God. You cannot look at that picture without just feeling so much incredible pain coming from her.

So, when passing it around I said, “This woman, when she was young, had been molested several times. When she was 15 she was put on oxycontin, from there she turned to heroin, she lived on the streets homeless in Portland, she'd been raped multiple times, she traded sex for drugs – through one of those times she became pregnant. She has attempted suicide, I don't know how many times, she's been incarcerated 22 times – many of those times she suffered incredible withdrawals where she puked and defecated herself for days and days, she currently lives day to day taking a fix just to get by.” Then I told them that she was my daughter.

There are hundreds like her. They calculated the national statistics that say that just the fact that you grow up on a reservation, you are 10 times more likely to commit suicide, become incarcerated, addicted and die an early death.

Lucy: It reminds me of the stages of genocide and in particular of one of the stages after the oppressor abuses those targeted for years, taking away the things that are the most important to those targeted and enacting years and years of abuse. The perpetrator leaves after doing such a deep job of infecting and internalizing colonization and self-hatred in the community. The pain is so deep. The harm and the wound is so deep that the perpetrator leaves and lets the community self-destruct. There are narratives that judge a community when this happens, accusations that the community is screwed up when it is just reacting to the trauma that has been enacted on it for so long. Richard Rohr says pain that is not transformed will be transferred. This didn't just happen, right? The judgement becomes another level of abuse.

Denise: We have these reservations, and we have huge rates of poverty, we have huge rates of incarceration, we have a lack of health care. People think that we get free health care because of the Indian Health Service, well, the health centers are on what they call "priority 1," which means if you are not threatened with losing your life or a limb, you do not get referred to any specialist, you do not get referred to any kind of tests like CAT scans or special testing if you don’t have insurance, because they cannot afford to pay the bill. The only access you have is on-site care, which means dental, mental health, and an on-site physician who can see you for minor ailments, but they’re not a specialist. It means that if you have cancer it’s not going to be detected. That's something that people out there believe that we have, this free health care system for everyone, and that's not true. We have a total lack of healthcare which is another form of genocide. And then we're penalized for telling the truth.

Christina Elcock: Thank you so much for sharing that, Denise. As kind of a continuum of what you were saying, what are the other deep-lasting impacts of colonization in U.S. culture?

Denise: I think what's imposed in the system of government, a culture where land is seen as something that people have a right over. Land is seen as something that is owned and used to get more wealth by either selling it or extracting resources from it – like industrial farming, mining, tourism and that kind of thing. There's a belief that wildlife and living things are inferior to humans, that it's okay to keep infringing on their living space. The mentality is that you don't just hunt to feed yourself, you hunt for sport and entertainment. There's a separation from the beauty of things and the suffering of living beings, there's no conscience.

I think it's really sad when people don't really know themselves because they're so preoccupied with making money and collecting more stuff, they just want more, more, more. People compete with each other all the time. They think they have the right to everything. There's this mindset of superiority, of value, and profit. Making money is more valued above anything else, the systems and laws have been built and created to benefit white people and there's no acknowledgement of the harm that it does to people of color (POC) or the harm that it has done to Black people, like slavery. There has to be a separation from people, a separation of a part of themselves, from their own humanity, for them to be able to continue to act this way.

Related posts

Thinking about decolonization as Thanksgiving approaches: A conversation with Denise Altvater part 1

Decolonizing our hearts and minds as people of faith: A conversation with Denise Altvater, part 2

Healing does not require forgiveness: A conversation with Denise Altvater, part 3

Acknowledging the full truth of our past: A conversation with Denise Altvater part 5