AFSC Michigan staff and family (from left) Pete Martel; Natalie Holbrook-Combs; her daughter, Willa; a cutout of Natalie’s wife, Tashiena Combs; Adalia Kirby; and Claudia McLean. Not pictured: Staffers Lawanda Hollister and Cozine Welch. Photo: Jon Krieg/AFSC

Everyone deserves a second chance. We all should have the opportunity to rebuild our lives, reconnect with our families, and strengthen our communities. For people serving life and long sentences, however, that second chance almost never comes.

AFSC is working to change that. Our Michigan Criminal Justice Program is led by people inside prison, their loved ones, and people who were formerly incarcerated. The program is also the lead advocate for “Second Look” legislation in the state, which would give many more people the chance to come home.

The bill would allow people who’ve served 10 years or more to petition for resentencing and another chance at freedom. If a person’s sentence is reduced, that person would still be required to serve every day of their new minimum sentence before they are considered for parole.

As recently as 2007, Michigan imprisoned 51,000 people. Today, largely thanks to paroles, the number of people inside is 32,000. Yet nearly half of the people remaining are serving life or very long sentences and have very little chance of release—all at a cost of $46,000 taxpayer dollars per person each year.

Supporting women in prison

While AFSC advocates for all people in prison, the Michigan program focuses on the 1,600 people locked up at Women’s Huron Valley prison, just a few miles from the AFSC office in Ypsilanti. About one-third of these women are serving excessively long sentences, and 200 have life without parole.

Far too often, the needs of women in prison are overlooked by correctional authorities and advocates. For instance, while the average age of a man sentenced to life is around 20, the average age for a woman is over 31. Women are often incarcerated later in life because they hit a tipping point after surviving years of violence, says Pete Martel, AFSC associate program director and an attorney. “With all the abuses and traumas they’ve suffered, they snap and say, ‘Enough is enough.’”

One in three women in the U.S. have experienced sexual violence between the ages of 5 and 25. This trauma impacts brain development, says AFSC program director Natalie Holbrook-Combs. Under the “Second Look” bill, people who’ve experienced domestic violence and sex trafficking can build that into their case when they go for resentencing.

In addition, 40% of women in prisons and jails across the U.S. identify as lesbian or bisexual, Natalie says. Politicians who care about the needs of the LGBTQIA+ community—including Michigan’s current governor—need to pay attention to people inside prison, too.

Both Natalie and Pete act from experience. Natalie is married to Tashiena Combs, who is serving a life sentence and is a strong abolition advocate from inside prison. Pete served a number of years in prison in Michigan—including a long stint in solitary confinement—prior to his AFSC service and law school.

Other team members have firsthand experience, as well. Lawanda Hollister, now a statewide organizer for AFSC, went to prison at age 17 and served 34 years. Cozine Welch, 43, also went in at age 17 and served 20 years. While incarcerated, he was active with the University of Michigan’s Prison Creative Arts Project for 11 years. Since their release, Lawanda and Cozine have been connecting their work on the street with legislative efforts, partnering with organizations across the state to pass Second Look legislation.

The power of storytelling

Families and community members rally in support of “Second Look” legislation in Michigan. Photo: Shakeb Ahmed

AFSC staff and their loved ones are just some of the thousands of formerly incarcerated people in Michigan who show what is possible with a second chance. Putting a human face on the issue of life and long-term sentences is a key part of AFSC’s work. Reminding politicians and the public about our common humanity is critical to building support for change.

Last year, AFSC and partners launched an online storytelling initiative “Let Me Tell You,” which shared the stories of incarcerated people and their loved ones in Michigan. Team member Adalia Kirby directs the program’s commutations project. She helps collect the stories of women in prison who share—through letters—why they deserve commutation.

For many people, medical reasons are paramount. People who reach their 50s in prison are considered elderly because of the harsh conditions of confinement.

“I have firsthand experience of having parents in prison and how that affects their children,” Adalia says. “I beat a lot of statistics. I’m a rarity—going to college and having this job. I understand the importance of this work.”

Her colleague, Claudia McLean, is a recent graduate of the University of Michigan and AFSC’s Second Look coordinator. Over the summer, she organized community barbecues across the state. These social events help connect legislators with their constituents who’ve been incarcerated and/or have loved ones inside.

At the heart of AFSC’s work for Second Look and commutations lies the belief that punishing people for decades or their entire lives not only hurts individuals, it weakens our communities and society at large. Changing the narrative about people serving life and long-term sentences is work that AFSC is committed to for the long haul.

Says Natalie, “The work we’re doing out in the community and internally asks, Do we really want to punish people for the rest of their lives? Is that what we do when someone causes harm?”

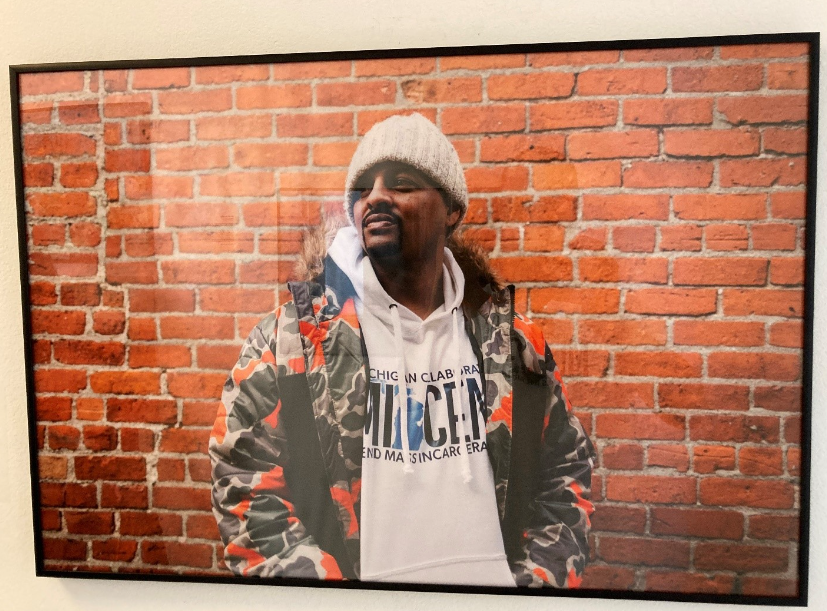

A portrait of Danny Jones, a former AFSC staff member and former lifer who died last year. This portrait -- and those of Natalie Holbrook-Combs and Pete Martel by photographer Sean Wilkinson -- were part of the exhibit “Free Your Mind: Art and Incarceration in Michigan” at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Detroit.

Read more articles by AFSC staffers:

- Opinion: Second Look legislation can fix Michigan’s criminal legal system by Cozine A. Welch Jr.

- Column: Give Michigan judges the opportunity to review long sentences by Natalie Holbrook-Combs and Maya Menlo